“Our ambition is to be the cloud of investment management in technology.” - BlackRock CFO Martin Small

In 1988, BlackRock was born under the umbrella of Stephen Schwarzman’s now $1T private equity juggernaut, Blackstone. As Robin Wigglesworth explains in his excellent book on the passive investing industry, Trillions, Larry Fink, a former MBS trader at First Boston, and Ralph Schlosstein, an investment banker at Shearson Lehman Hutton, set out to build an investment firm that would try to model every single security in order to build portfolios and manage risk for their clients.

Starting with a bond fund, BlackRock has become the largest asset manager in the world. As of their 2022 Annual Report, BlackRock manages ~$8.6T across ETFs, index, and active strategies. This has led to no shortage of attention from Wall Street to Main Street to D.C.

As Fink and Schlosstein set out to raise their first bond fund, they started building a technology platform that would help with their portfolio management. It was called the “Asset, Liability and Debt and Derivative Investment Network” or Aladdin. By 2020, Aladdin had $21.6T in its platform which made up about 10% of global stocks and bonds. The other two major asset managers, Vanguard and State Street, use Aladdin. So does Microsoft’s corporate treasury and BNY Mellon as a custodian bank. It was even used as a part of BlackRock’s work with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. It makes up a bulk of BlackRock’s technology services unit which brought in ~$1.4B in revenue.

As an early-stage software investor, I spend a lot of time thinking about what the world will look like in the coming years and where technology can solve long-term problems. In finance, Aladdin presents a blueprint for the coming platformization that will reshape how money is managed.

So, what is Aladdin, really?

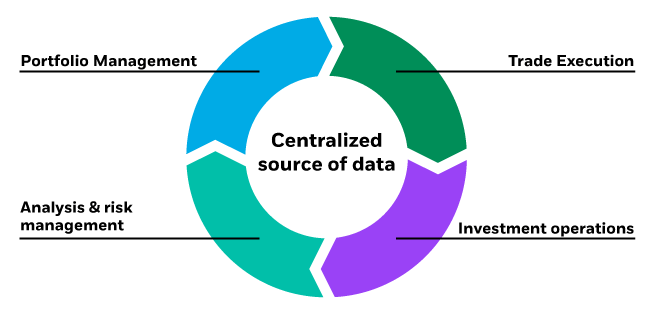

According to BlackRock, “Aladdin is a tech platform that unifies the investment management process—through a common data language—to enable scale, provide insights and support true business transformation.” This manifests in four main segments:

Blackrock’s representation of Aladdin’s core feature set

Aladdin has the ability to model risk across various asset classes. It can watch for portfolio exposures, handle stress-testing, value securities, and calculate performance across benchmarks. It can produce US GAAP and other base accounting reports, monitor end-of-day compliance rules, and help optimize asset allocation.

Then there’s Aladdin Studio, an API-driven offering that allows clients to develop custom models, generate workflows, and perform research on their data from Aladdin. Clients with a lot of data inside and outside of Aladdin can now also use the Aladdin Data Cloud, a joint-offering with Snowflake that is basically a custom Data Warehouse for BlackRock clients.

Aladdin, today, is an increasingly automated SaaS product that turns manual portfolio management services into quick workflows with little human intervention.

What about AI?

7 years before Larry Fink started BlackRock, another trader, Michael Bloomberg, set out to build a financial data system. Bloomberg, who had recently been fired by Salomon Brothers where he had built internal computer systems, launched Innovative Market Systems, later Bloomberg LP, to offer access to high-quality financial data through computer terminals to Wall Street firms starting with the brokerage Merrill Lynch.

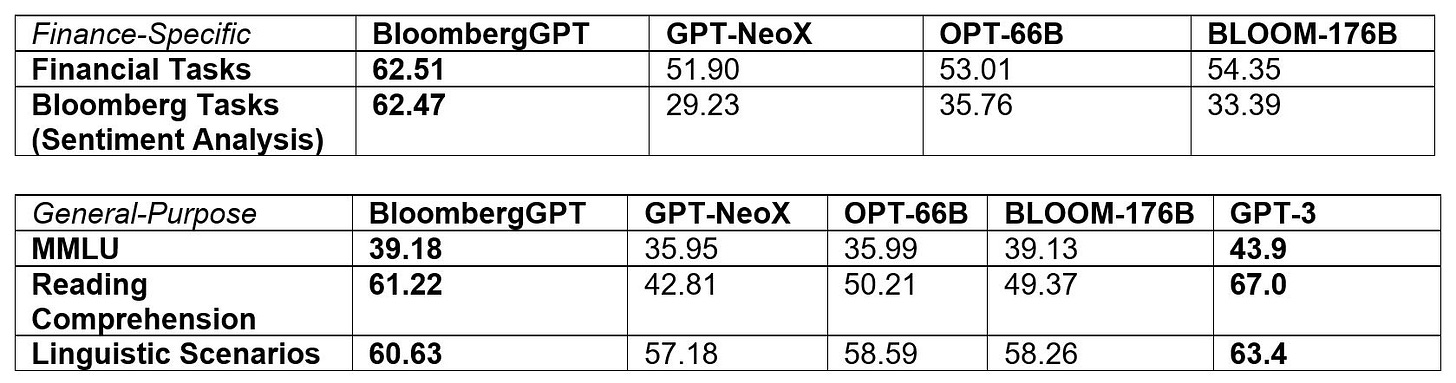

Today, the company brings in over $12B revenue and is still the go-to data source for investment firms. And in March of this year, Bloomberg launched BloombergGPT, a 50B parameter LLM that performs better than it’s peers on finance-specific tasks.

BloombergGPT vs. it’s LLM peers across general and finance-specific tasks

Why does this matter for startups? Bloomberg has two key advantages: data and screen real estate. This leads to a great flywheel: the more people use Bloomberg, the better the feedback they have for AI and the better their AI and data, the more people want to use Bloomberg.

For traders, Bloomberg is their gateway to finance and this allows Bloomberg to upsell all sorts of products to them from news to alternative data. Any startup that wants to build for financial institutions will either need to build alongside Bloomberg or find a niche where they can have a real edge.

So where can startups build?

I’d bucket the markets ripe for disruption into 3 main categories: capital markets & trading, data, and embedded finance.

Capital Markets & Trading

Capital markets and trading solutions are struggling for two main reasons: outdated technology and the innovator’s dilemma. Today’s markets are faster and more complex than ever before and systems that run on COBOL just don’t work.

Banks and existing brokerages also often don’t want to change because they still make money off the inefficiencies in the market. Public credit is a great example of this. Even though, the NASDAQ was launched 53 years ago as an all-electronic stock exchange, credit lags behind. Today, just 45% of investment grade and 30% of high-yield corporate bonds are traded electronically. And while bonds settle T+1 like stocks, leveraged loans, a type of commercial loan to businesses with existing high amounts of debt, settle on an average of 19.5 days. But, while banks have ceded the role of market maker to folks like Citadel Securities in equities, they still make money as market makers in credit.

Some startups that have taken advantage of these opportunities are Clear Street, a modern prime brokerage, and Trumid, a credit trading market. I also should mention that Citadel Securities, the largest US retail market maker with 35% of trade volume, raised money from traditional venture firms, Sequoia and Paradigm.

Data

As I mentioned earlier, data is an increasingly important commodity for the development of AI models. Finance is also a highly quantitative business that values proprietary access to data. dv01, a provider of loan-level data, was acquired by Fitch Solutions. Preqin, a provider of alternative investment data, was bought by BlackRock for $3.2B this summer. And Pitchbook parent Morningstar, spent $600M on LCD, a credit data provider, to buy it from S&P Global and offer it through Pitchbook. This is a tough market to compete in as you need some edge to be able to acquire proprietary or tough-to-access data.

Embedded Finance

Basel III Endgame is a regulatory framework focused on reducing risk on bank balance sheets by making them hold more capital. This has pushed lending activities from bank balance sheets to private credit funds and insurance companies. The large asset managers like Apollo and Ares have gotten into the business with significant scale and cheap capital through annuity businesses. That prompted Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, to say that these firms are “dancing in the streets” over increased bank regulations.

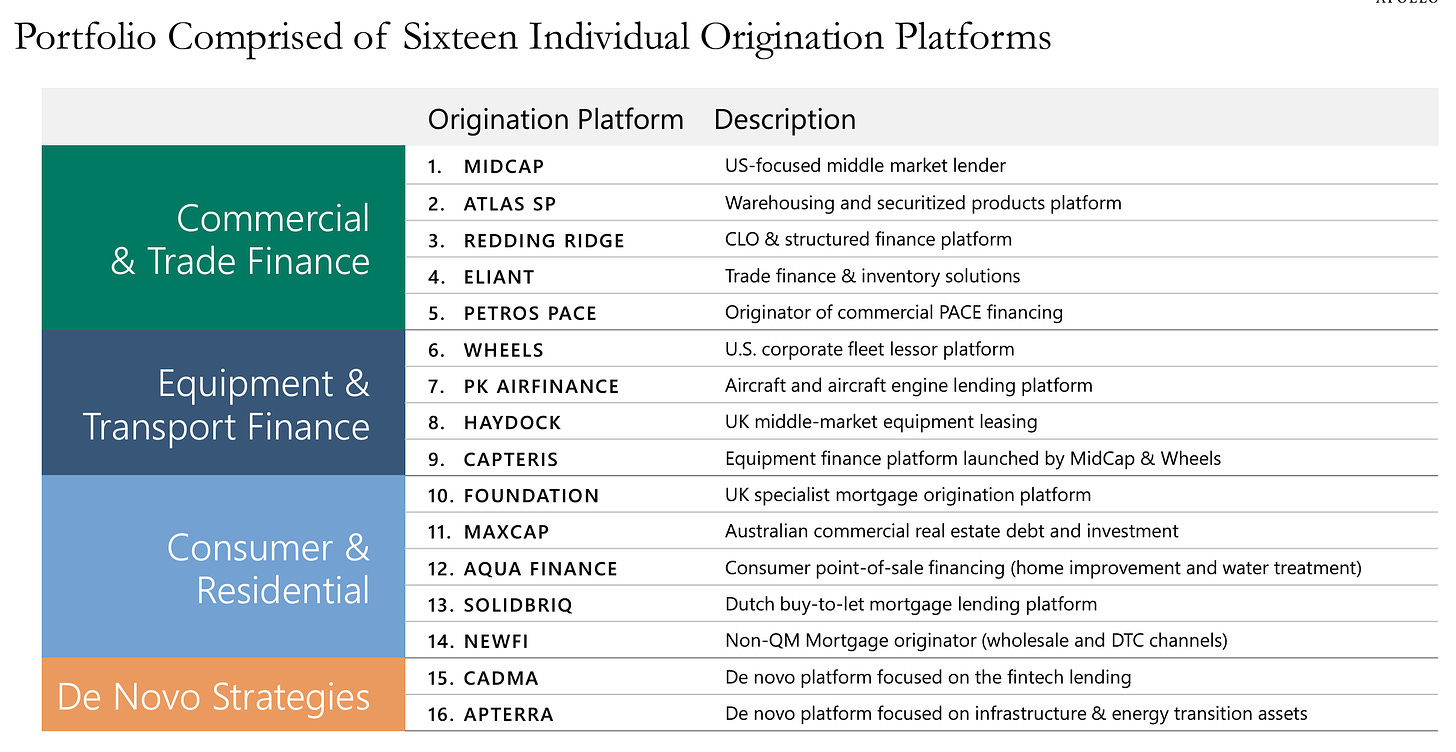

The asset managers have a problem, though: their annuities businesses are larger than their private credit origination capabilities. Apollo manages $350B+ in Insurance AUM and has 16 unique origination platforms to create private credit deals that can be kept or securitized and sold. They range from Atlas SP, the structured credit firm Apollo bought from Credit Suisse, to Cadma Capital Partners, a venture-focused origination platform.

Apollo’s 16 different origination platforms outlined in an investor presentation

This opens up an opportunity for fintech startups. Embedded lending solutions are API-driven lending platforms often used by vertical SaaS platforms. This can lead to creative structures. For example, Toast’s loans to their clients are paid off based off of daily card sales which Toast has access to as a POS system. These solutions can partner with capital providers like annuities firms. Many consumer fintech companies look like debt originators that could partner with private credit funds as well.

There is such a large opportunity to serve financial institutions with better technology. If you’re building in any of these areas, please reach out!